Word Vignette

Daguerreotype

Taking pictures, whether it be selfies or photos of other people, is a mainstay in our life. We document our daily lives through the camera lens on our phones, but that was not always the case. Photography is a relatively new concept in the history of humankind with its beginnings in the daguerreotype, the first widely used and successful form of the photographic process (Brittanica.com). Merriam-Webster defines it as “an early photograph produced on a silver or silver-covered copper plate.” These marked a turning point in how people recorded likenesses, history, and memory. Unlike painted portraits or sketches, the daguerreotype provided an unprecedented level of realism, forever changing the way humanity saw itself. But where did this word come from?

Etymology & Evolution

Daguerreotype is a compound word taken from its inventor, Louis‑Jacques‑Mandé Daguerre, and the word type. The first known use of the word daguerreotype is in 1839 when this silver-covered copper plate with an incredible detailed likeness of its subject was introduced in France, however, each part of the word goes back much further.

Daguerre is from the inventor’s name. This surname traces back to Spain in the Middle Ages and was derived from localities that denoted the proprietorship of a village or estate, so the Daguerre family were in a noble or prominent place within the village they came from. A descendent of this family is Louis‑Jacques‑Mandé Daguerre. (House of Names)

The latter half of daguerreotype, the suffix –type, is rich in history. Its roots lie in the Greek typos, meaning “impression,” “mark,” or “figure formed by a blow.” This earliest sense is something physical like the indentation left in wax or clay or the mark of contact between object and surface. From Greek, the term passed into Latin as typus, retaining the notion of a visible image or form. By the late Middle Ages, the meaning of type began to shift. The word evolved from referring to a literal stamp or mold to describing a printed character or an image transferred by pressure. This connection foreshadows its later resonance with photography as processes of replication and impression, of fixing a pattern into permanence (etymonline)

The Shift Away

By the 1860s, new technologies such as the ambrotype and tintype, followed by albumen prints from glass negatives, began to replace the daguerreotype. In time, the word also faded from conversation, yet its etymological echo remains, a reminder that language, too, holds its own photographs of the past.

Cultural Echoes

Though its era was brief, the daguerreotype remains iconic. It represents photography’s birth and humanity’s first true attempt to capture time in silver and light. Today, museums and collectors preserve these images not only as works of art but also as cultural artifacts. Reminders of a moment when the world first learned to see itself with unblinking accuracy.

Click on the link to see some of these images: Daguerreotype: History’s First Successful Photographic Process

I’m sure many families have images of their ancestors captured on daguerreotypes either prominently displayed, or hidden in attics, in the folds of old family Bibles, or in old wooden boxes along with other family relics. I found some in a Bible that once belonged to my great great aunt on my father’s side where I can see our family’s likeness captured in the images.

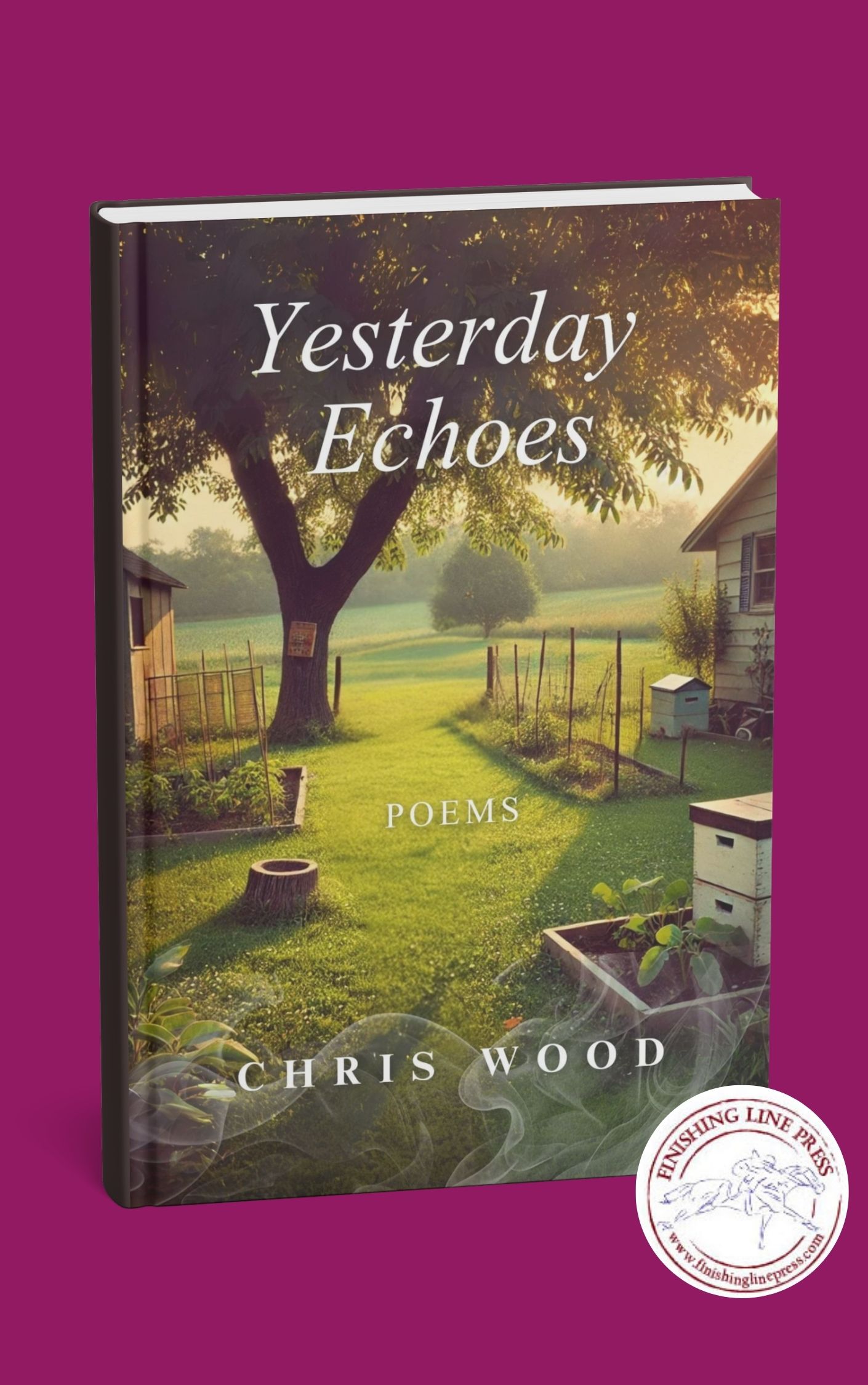

I share this in my poem, Heritage, from my debut poetry collection, Yesterday Echoes.

“I see their names written

— Excerpt from Heritage by Chris wood

between the Old and New Testaments,

King James written in Elizabethan script.

Faces, printed on daguerreotypes

tucked in the Books of Judith

and the Maccabees, show the shape

of my eyes, blue, a trait held

in my father’s genetic material,

carried from my grandfather.

While the word itself drifted from daily language, the daguerreotype’s cultural echoes ripple into our present age. In its time, the daguerreotype allowed families to possess a portrait of a loved one, a tangible, silvered record of a face and a moment. Just like when we write, we record those moments of the past to remember. Words, just as portraits, preserve when all else fades.

Today, of course, photographs and words surround us in every form: digital feeds, albums, social media, but also artful prints. We still crave the stop-moment in time, the reflection of “who we were” and “who we are.”

And so, the mirrored plate of memory lives on, resonating anew in each image we make and each word we write.

Sources and further reading…

- “Daguerreotype | Portraiture, Early Processes, Silver Plating.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/technology/daguerreotype.

- “Inside the Eerie World of Daguerreotypes, the First Photographs Ever Made.” All That’s Interesting, 28 May 2024, https://allthatsinteresting.com/daguerreotypes.

- “Daguerreotype.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/daguerreotype.

- “Daguerreotype – Etymology, Origin & Meaning.” Online Etymology Dictionary, Etymonline, https://www.etymonline.com/word/daguerreotype. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025. (Etymology Online)

- “Daguerre Name Meaning, Family History, Family Crest & Coats of Arms.” HouseOfNames, House of Names, https://www.houseofnames.com/daguerre-family-crest. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025. (House of Names)

- “Type – Etymology, Origin & Meaning.” Online Etymology Dictionary, Etymonline, https://www.etymonline.com/word/type. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025. (Etymology Online)

- “TYPE Definition & Meaning – Merriam‑Webster.” Merriam‑Webster, Merriam‑Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/type. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

- “type, v. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary.” OED Online, Oxford University Press. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025. (oed.com)

- “Daguerreotype.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daguerreotype. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025. (en.wikipedia.org)